Exploring Black Life and African American Art at the Marciano Art Foundation in Los Angeles

During a recent visit, NOMMO explored the Marciano Art Foundation on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, CA. Once a grand Masonic Temple, this historic landmark now thrives as a vibrant museum, inviting the public to engage with its extensive collection and immersive exhibitions.

In alignment with NOMMO’s mission to illuminate African American art, history, and culture, the Marciano highlights works by celebrated artists such as David Hammons, Mark Bradford, Glenn Ligon, and Deana Lawson, whose portrayals of Black life demand recognition and reverence. The collection also includes works by artists like Kelley Walker, whose Black Star Press reflects on Black life and the civil rights movement, showing how media and representation continue to shape historical understanding.

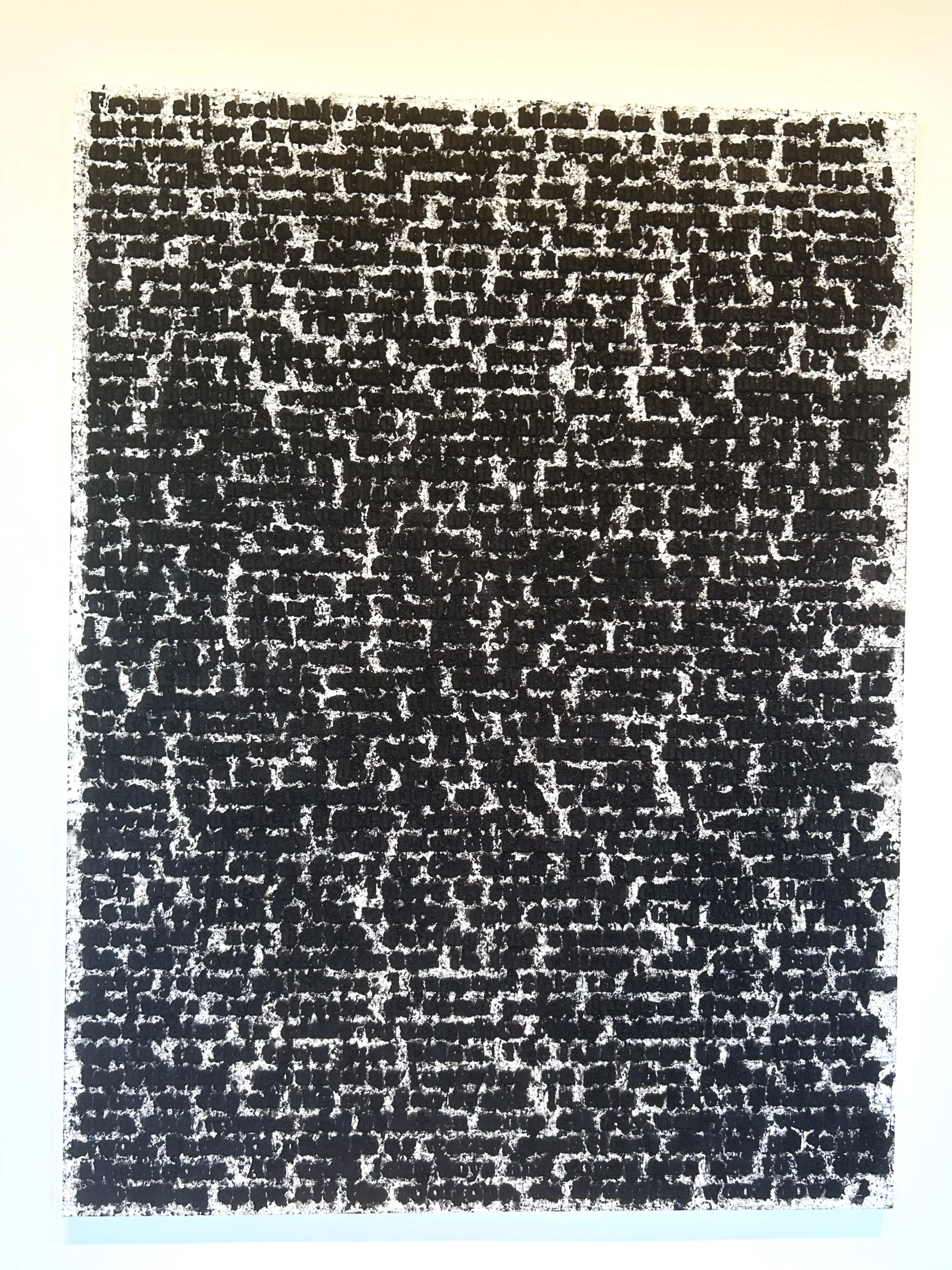

Glenn Ligon — Stranger #78

At the Marciano, Glenn Ligon’s #78, made with coal dust, offers a powerful exploration of political differences and ideas of belonging, highlighting his use of this material as both a favorite and a metaphor. This series, inspired by James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village,” which he began in 1997, features stencil passages on canvas covered with coal dust and glue until the words nearly disappear. The dark surface makes the text almost unreadable, physically embodying Baldwin’s central question: Who, in the end, is the stranger? This work hits the viewer where they stand.

David Hammons — Untitled Works

David Hammons: Untitled, 2010. Acrylic on canvas and tarp, 103 x 80 inches.

On view at the Marciano, viewers can see that the enigmatic David Hammons commands a powerful presence within the galleries. Whether it's the monumental Untitled (2010), a canvas-and-tarp piece dominating a second-floor wall, or the striking Untitled (2007) fur coat embedded with acrylic and spray paint, Hammons’s works resist simple classification. They function on both personal and collective levels, encouraging viewers to reflect on the connections between the artist’s inner world and the real-life experiences of Black Americans.

David Hammons: Untitled, 2007. Fur coat with acrylic and spray paint.

Deana Lawson — Afriye

Deanna Lawson, Afriye: ,2023. pigment print.

Difficult to neatly classify, Deana Lawson’s work at the Marciano’s second-floor galleries straddles photographic tradition and social collaboration. Afriye (2023) places as much emphasis on Lawson’s intimate exchange with her subjects as on the resulting image. Its mirrored frame amplifies the gaze of the two figures while reflecting our image, making us participants in the act of looking.

This interplay recalls Diego Velázquez’s iconic Las Meninas (1656), which also stages a complex relationship between artist, subject, and audience through a mirror. By extending this self-reflexive gesture into a contemporary and deeply personal context, Lawson transforms Afriye into a temporal bridge—connecting private Black spaces to a broader lineage of image-making and creating a powerful arena for self-definition.

Mark Bradford — Building “The Big White Whale”

On display at the Marciano, Building “The Big White Whale” (2012), Mark Bradford employs his signature collage technique, layering found paper, string, paint, and urban ephemera to create a monumental surface that feels both architectural and oceanic.

The title alludes to Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, turning the “whale” into a metaphor for vast, often unseen systems, social, economic, and racial, that influence and shape our lives. From a distance, the piece appears as pure abstraction; up close, it reveals fragments of advertisements, merchant posters, and weathered street materials, illustrating the layered histories embedded in the urban landscape. Bradford’s work combines literary allusions, personal memories, and collective history into a single, compelling statement.

Artists Engaging Black Histories

Kelley Walker — Black Star Press

Kelly Walker, Black Star Press (2006). Digital print

While not a Black artist, Kelley Walker’s Black Star Press (2006) revisits Charles Moore’s 1962 photo essay documenting civil rights protests in Alabama. Walker digitally reprints these photographs and overlays them with silkscreened chocolate, creating painterly gestures that obscure and amplify the violence depicted. The work reflects on how media circulate images of Black struggle and how the meaning of those images evolves across time and context.

Field Note reflection —

The Marciano Art Foundation’s presentation of these works offers a rare, concentrated space in Los Angeles to engage deeply with contemporary Black art. These pieces do more than exist on walls; they challenge viewers, bridge histories, and expand the language of what Black art can be.

As NOMMO continues its mission to champion African American art history and culture, we see immense potential in partnering with the Marciano to amplify these narratives further, through expanded programming, interpretive resources, and community engagement that honors both the artists and the audiences they speak to.

Why Afrospatialism™ Is Personal: Migration, Memory, and Black LA

The Personal Heritage of NOMMO’s Founder, Tyree Boyd-Pates, and the Legacy of Afrospatialism™ in Los Angeles, California

Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin of Nonstndrd Creative Projects (left) and Tyree Boyd-Pates of NOMMO Cultural Strategies (right) at LA Design Festival ‘25 in DTLA.

Last week, we introduced Afrospatialism™, our newest framework for reimagining Black space, and shared how it made its debut at the 2025 LA Design Festival.

This week, we explore the personal and cultural roots of Afrospatialism™ through the lived histories of NOMMO’s founder, Tyree Boyd-Pates, and his creative collaborator and Uncle, Kwasi Boyd-Bouldin of Nonstndrd Creative Projects.

At NOMMO, our work is rooted in the legacy of Black America. For both Kwasi and Tyree, Afrospatialism™ is more than a framework. It is an inheritance, shaped by their families’ journeys as part of the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans moved westward in search of refuge and possibility. For their family and other Black Angelenos, that journey culminated in Los Angeles, CA. But their families’ dream, persisted.

As Tyree shares:

“Our families weren’t just moving. They were fleeing. And what they hoped for wasn’t just survival. They imagined something freer for us. Afrospatialism is our way of protecting that dream.”

The Great Migration (% of U.S African American Population).

We approach our practice as sons of the Great Migration—that 20th-century exodus movement in which more than six million Black Southerners fled Jim Crow in search of safety, autonomy, and possibility. Our family was part of that historic exodus, guided by the quiet courage and vision of our matriarchs.

When Kwasi’s mother and Tyree’s grandmother arrived in South Central Los Angeles with her children in the 1980s, she carried more than just their belongings. She held onto an audacious hope that, as a Black family, they might live freer, fuller lives out West. For their matriarch, who was raised in Riceboro and Savannah, Georgia, during the era of American apartheid -when “Whites Only” signs barred her from water fountains, libraries, and public dignity, Los Angeles offered a sense of relief and promise that differed from both the South and the hustle of Northern cities like New York and Chicago.

Central Avenue street scene, Federal Writers' Project, 1939 Los Angeles Public Library

Feb. 18, 1986: A Los Angeles Police Department battering ram sits next to a South Los Angeles home damaged during a police raid.(Jack Gaunt / Los Angeles Times)

But Los Angeles was never a promised land. Like so many Black migrants to the city, our families encountered new forms of spatial exclusion: redlining, white flight, freeway construction, police violence during the War on Drugs, disinvestment, and, more recently, gentrification. And still, in neighborhoods like Crenshaw, Inglewood, Compton, Altadena, and even in unexpected pockets like Hollywood, Black families like theirs carved out vibrant communities and enclaves. These places remain sites of resistance, survival, and cultural brilliance, despite divestments.

After living in South Los Angeles, Tyree’s family relocated to the Koreatown neighborhood of East Hollywood, a densely populated area with a rich cultural and business history. There, he experienced the 1992 Los Angeles Uprisings firsthand, witnessing the clash of economic frustration, racial injustice, and civic neglect among the city’s diverse communities both during and in the wake of the civil rebellion. These early experiences shaped his path and laid the foundation for the language he would later develop as a historian and museum curator, as evident in his exhibitions, where he showcased the Black experience in Los Angeles within museum spaces. Tyree translated community concerns into spatial stories, using Afrofuturism to envision Black histories and futures where Black lives are not secondary but central to city, state, and national narratives. Notably, through his debut exhibition, "No Justice, No Peace, LA 1992," held in 2017 at the California African American Museum, he showcased his afrospatial work.

“Curation became my protest. Afrospatialism is the vocabulary I built to honor our ancestors while fighting for our right to remain, to dream, and to be seen in full.” — Tyree Boyd-Pates

“No Justice, No Peace, LA 1992” exhibit at the California African American Museum, 2017, curated by Tyree Boyd-Pates.

This is why Afrospatialism™ matters. It reflects on what Black Los Angeles has been, and reimagines what it can become. It invites us to dream, design, and defend Black space as sacred, inherited, and future-facing. Its lineage draws from creative ancestors like architect Paul R. Williams and writer Octavia E. Butler, who both imagined Black presence where it had been erased or unacknowledged.

Through NOMMO and Nonstndrd, both honor those who came before us, and lay a foundation for those to follow from LA and beyond. These futures are not only desired. They are reimagined to hold and maintain Black space with power and purpose beyond spatial confines.

Download the Afrospatialism™ Manifesto and discover how we’re reclaiming Black space through design, memory, and imagination here. Next week, we will reveal what incorporating Afrospatialism into practice looks like.