Witness and Repair: NOMMO’s Reflections on Greenwood and the Passing of Viola Fletcher

Photo: Gioncarlo Valentine for The Washington Post.

The passing of Viola Fletcher — the eldest known survivor of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre — marks a profound moment in our collective memory. Ms. Fletcher carried nearly a century of witness, offering the world an unyielding account of both the devastation she lived through and the justice denied to generations of survivors and descendants. Her transition reminds us that the work of truth-telling and repair remains urgent.

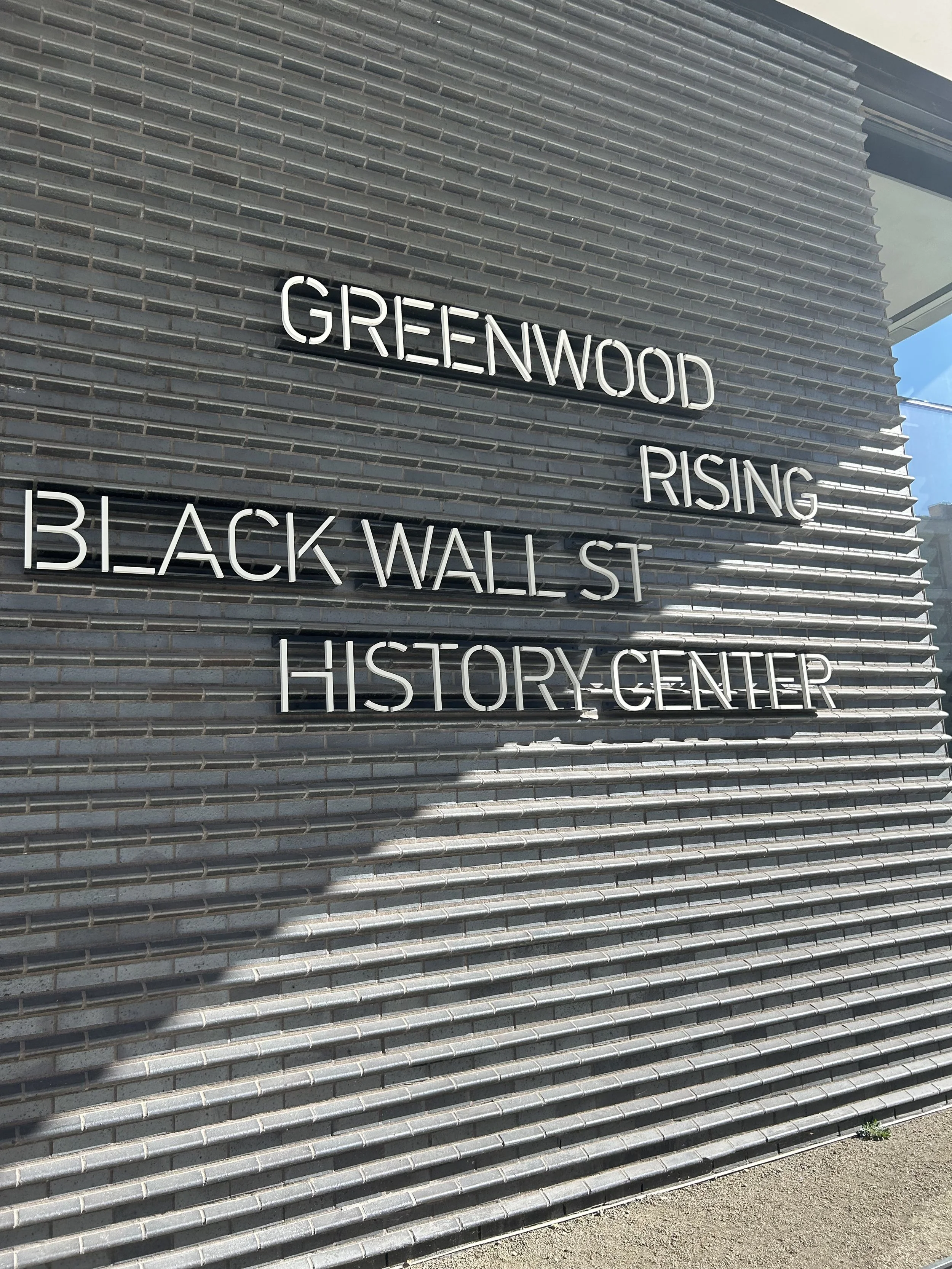

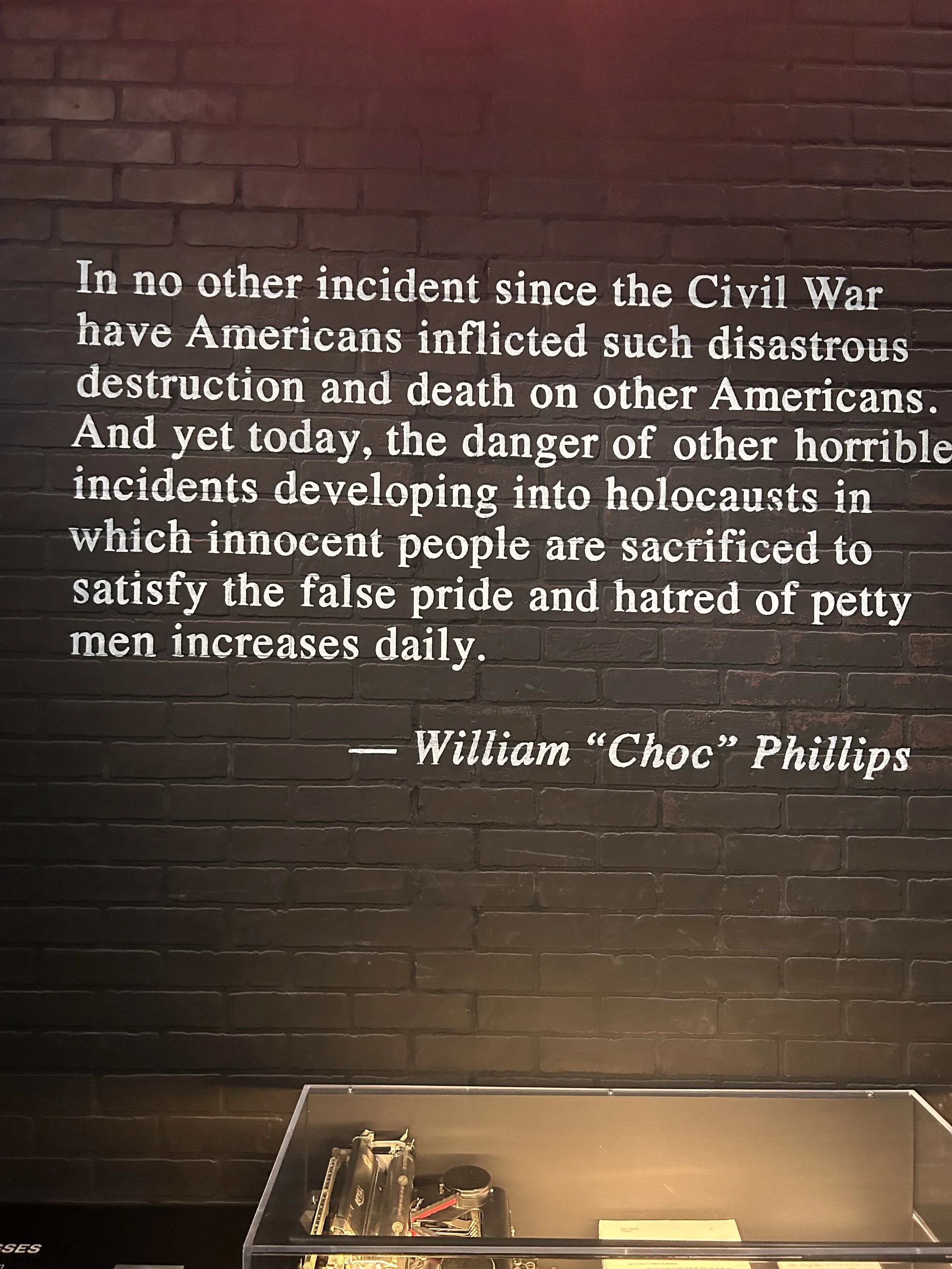

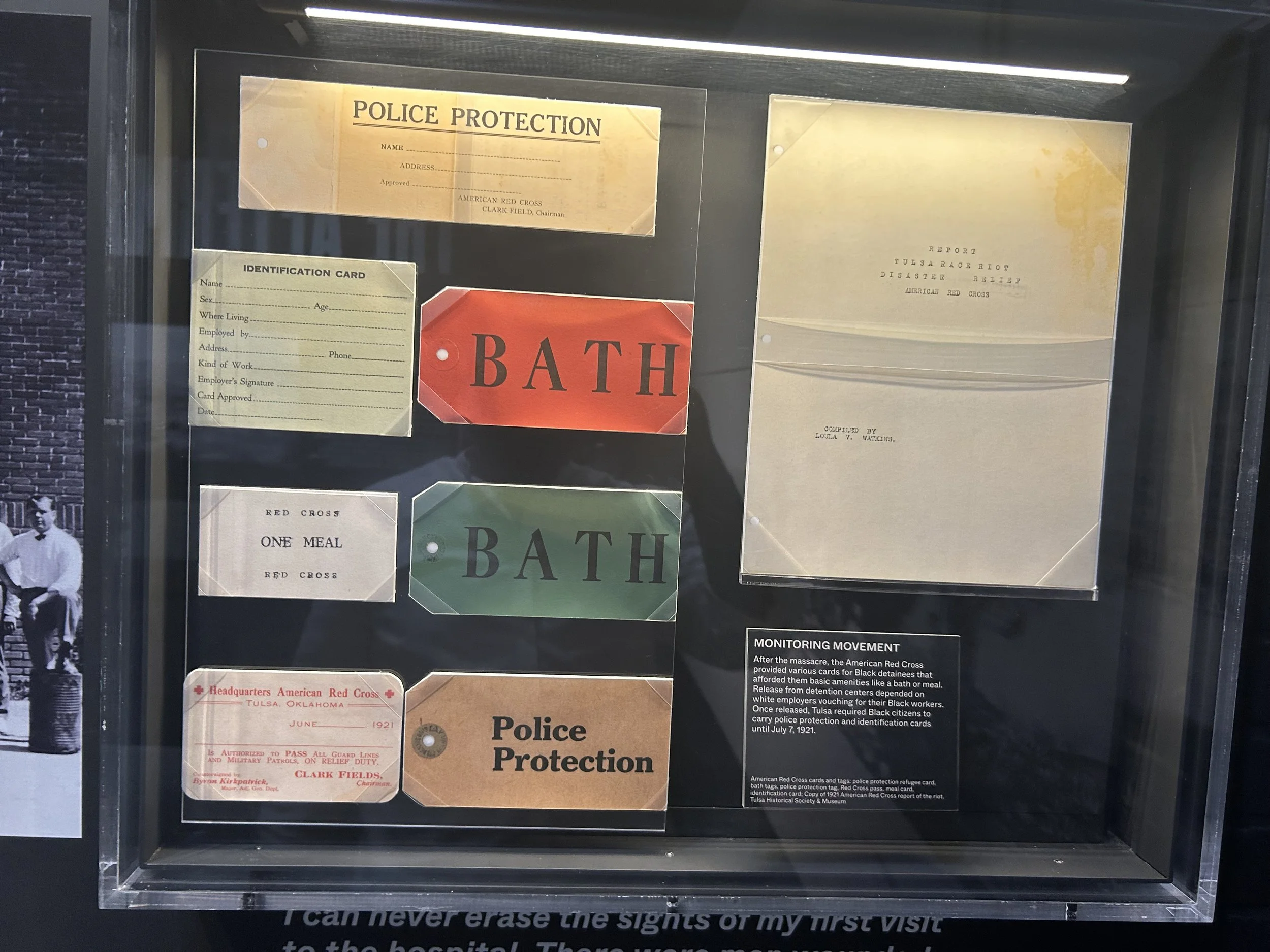

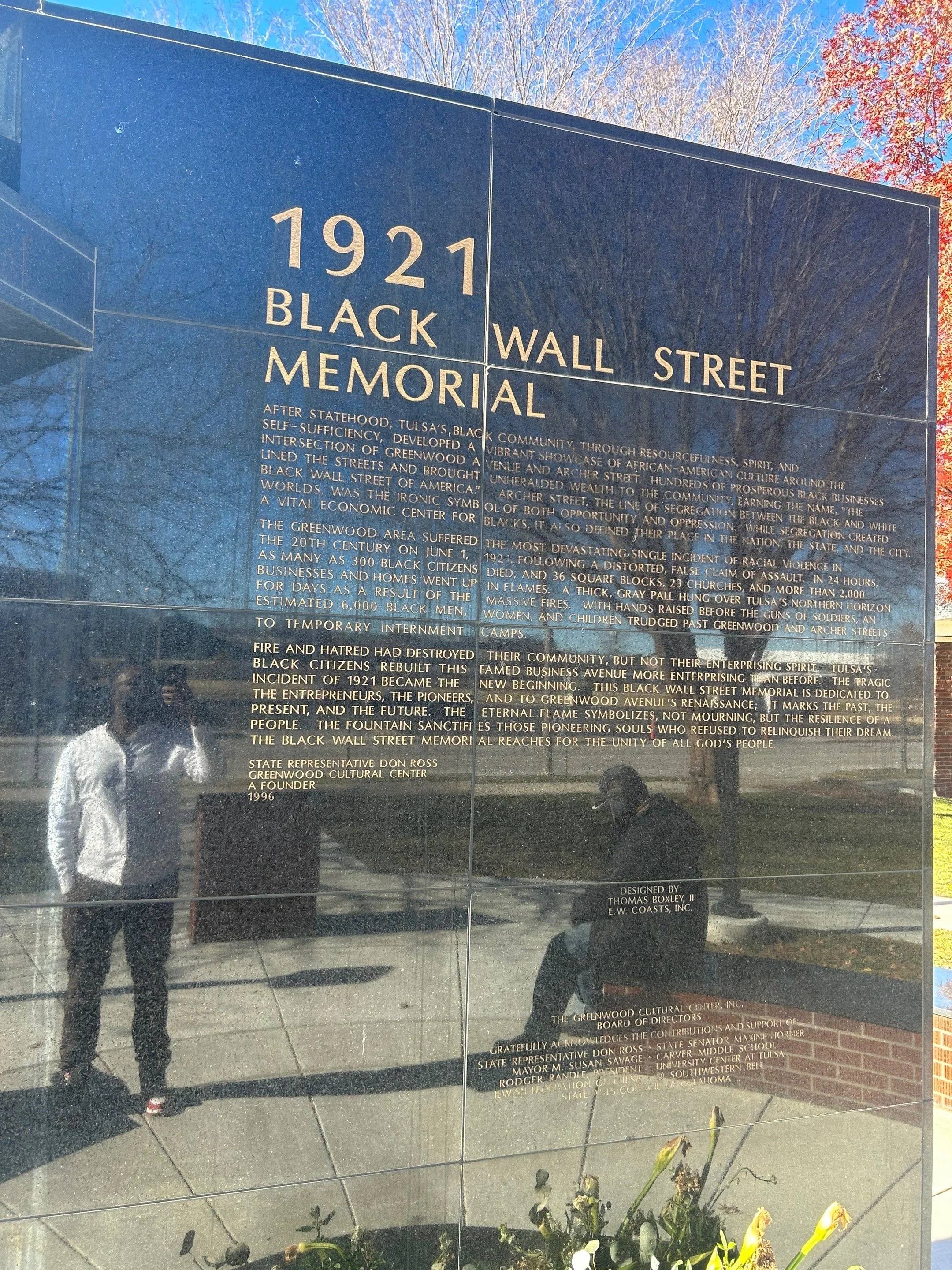

During a recent research trip, NOMMO visited the historic Greenwood District and toured Greenwood Rising, the site committed to preserving and interpreting the legacy of Black Wall Street. Standing on the sacred ground where brilliance, entrepreneurship, and community once flourished — and where racial violence attempted to extinguish it — brought renewed clarity to the stakes of our work.

Learning this history again in place underscores what the exhibitions at Greenwood Rising powerfully assert: the demands issued by 1921 are still with us. Repair is not symbolic; it is material, continuous, and anchored in accountability. The charge carried by Greenwood’s descendants, scholars, and culture-bearers mirrors a lineage of stewardship that NOMMO proudly aligns with.

Like Ms. Fletcher, NOMMO is dedicated to making sure that the memories of those who perished, survived, resisted, and rebuilt are not pushed to the edges. Their stories teach vital lessons about democracy, freedom, and the ongoing fight for justice in the United States.

In continuing these histories, NOMMO emphasizes that memory is active, serving as a practice of restoring lost or hidden stories. Our approach involves revisiting archives, land, and community testimonies to uncover what has been purposefully concealed. Greenwood highlights that the stories we carry demand guardianship, and that the cultural effort of truth-telling is deeply linked to ongoing struggles for justice, healing, and clear understanding of history. Through research, interpretation, and storytelling, we aim to present a more complete and truthful account of the past as a step toward building a fairer future.

As we celebrate Ms. Fletcher’s life and legacy, we also recognize the responsibility she leaves for us all: to preserve memory, confront erasure, and envision Black futures deserving of the ancestors who shaped this nation.

The Battle for America’s Memory: Lessons from MOCA and The Brick’s “Monuments”

How NOMMO interprets the cultural civil war unfolding in America’s art spaces — and what these monuments reveal about who we remember and why.

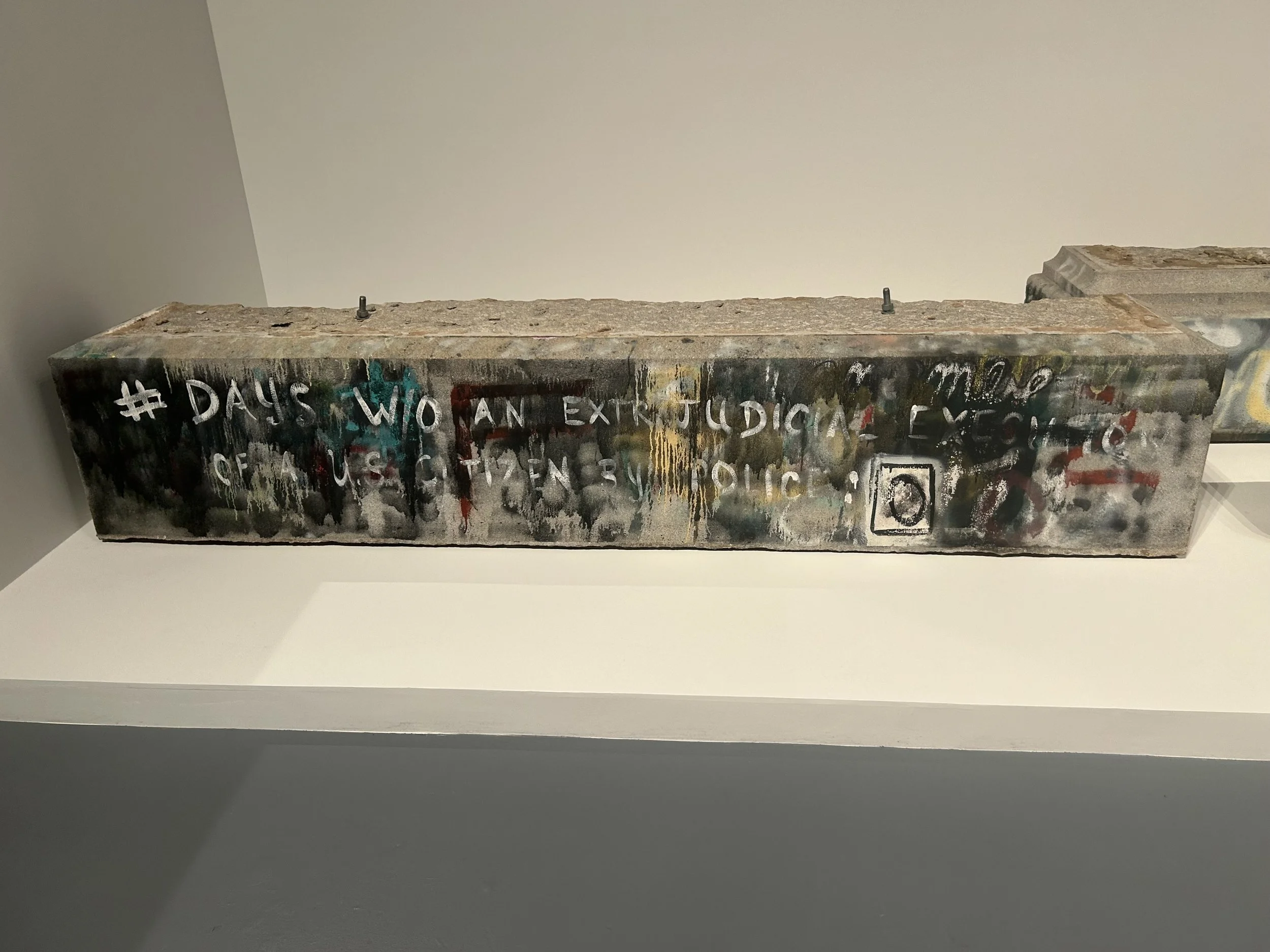

“Unmanned Drone,” Kara Walker, The Brick, 2025

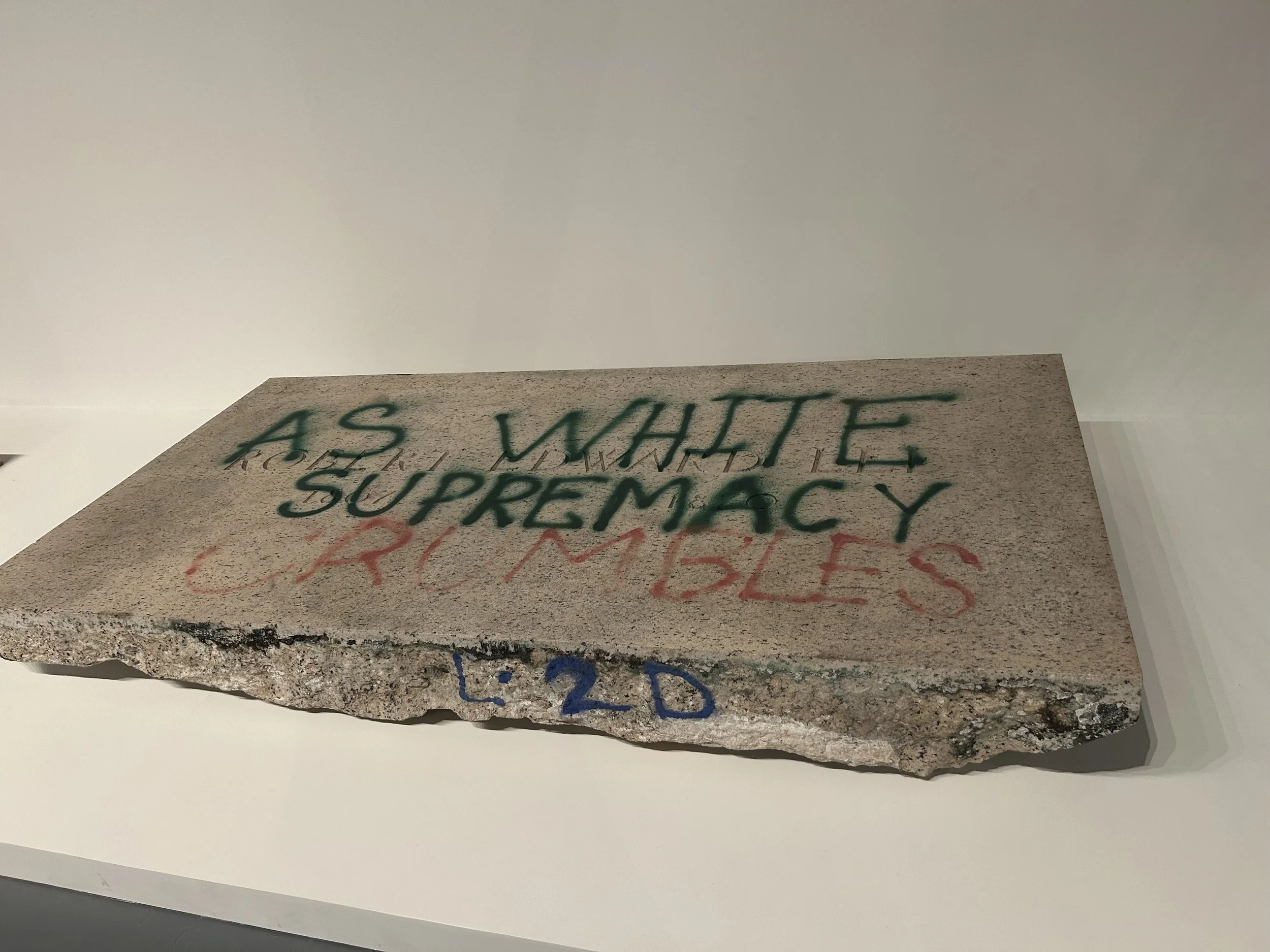

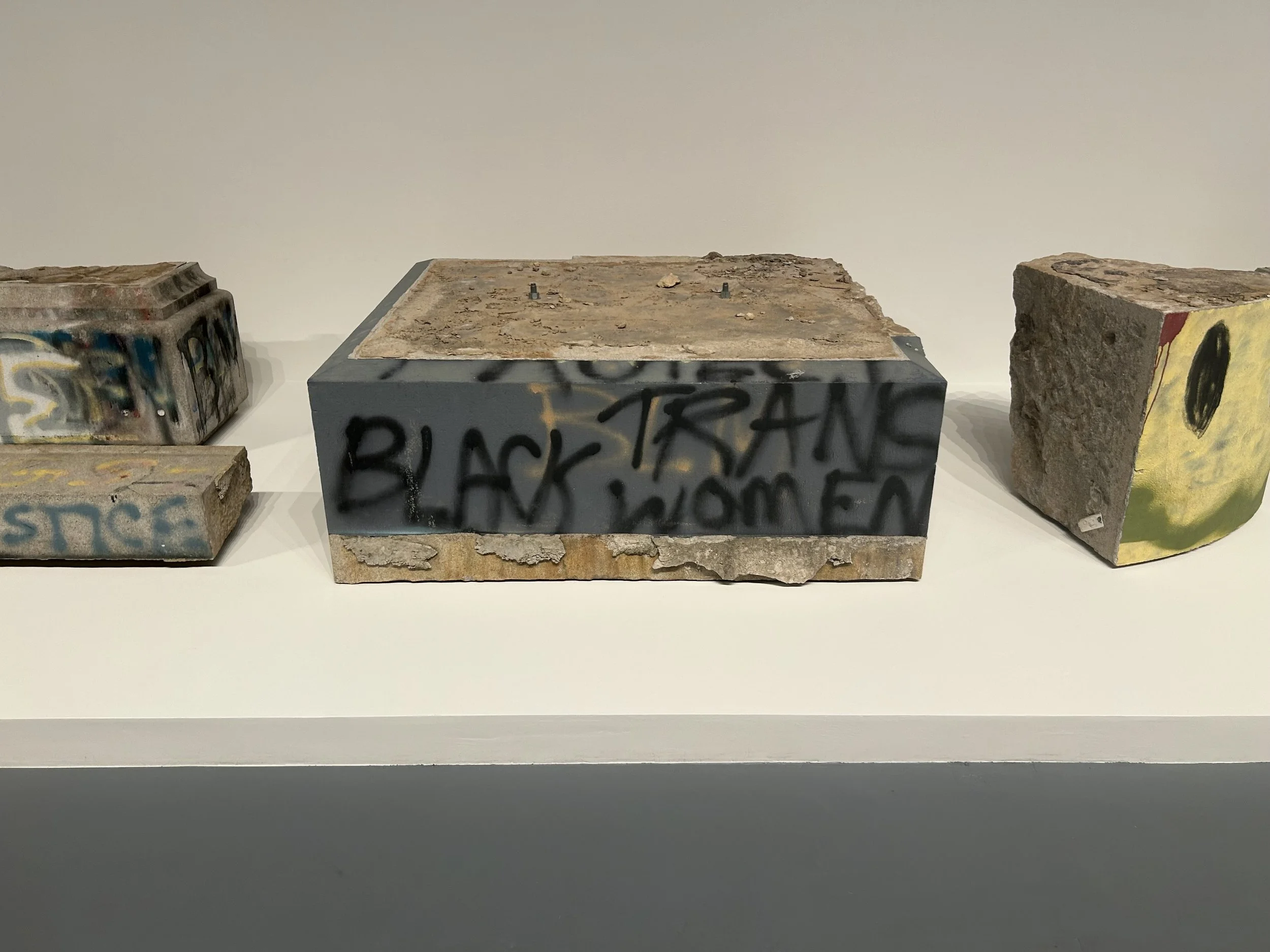

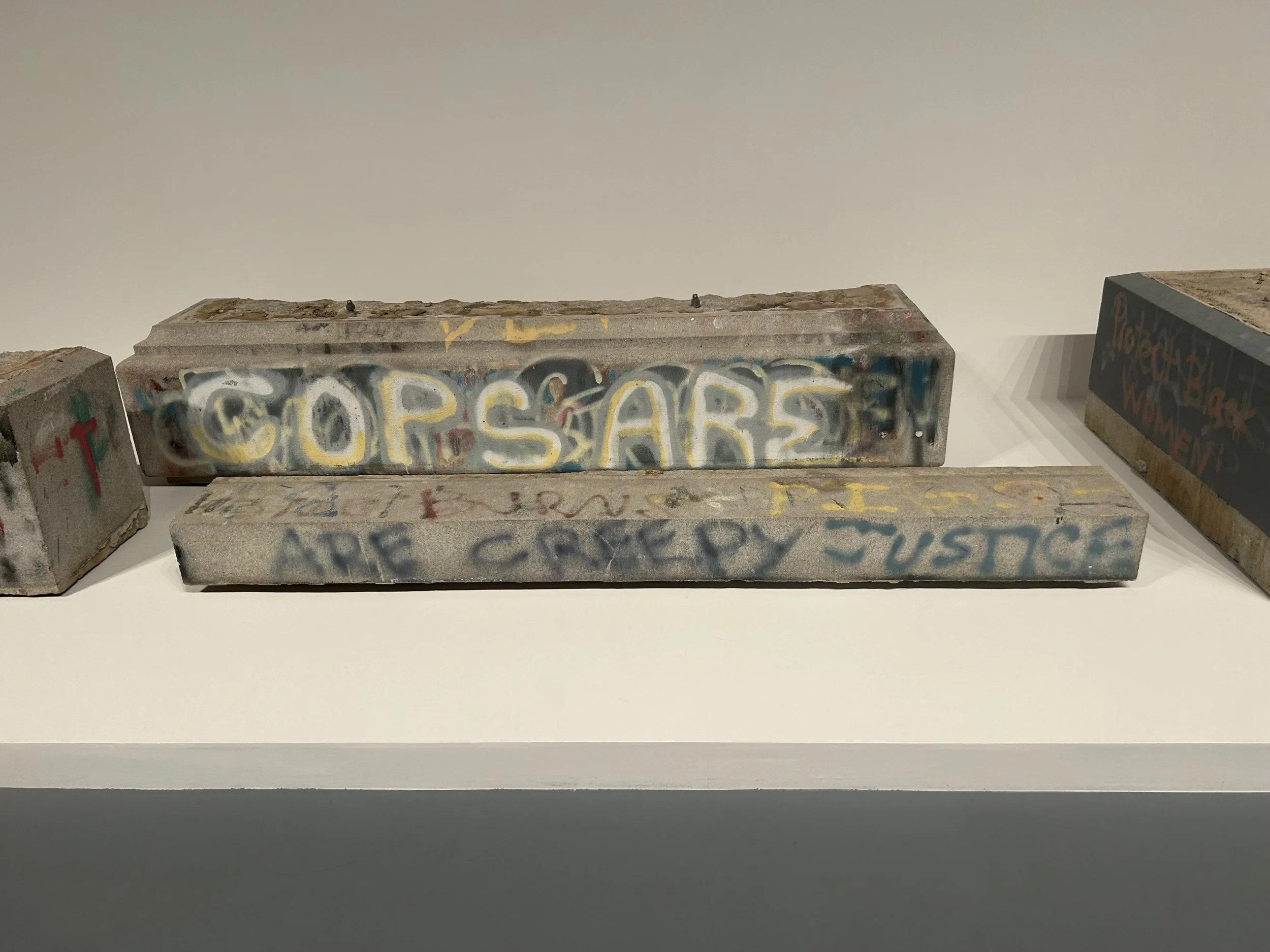

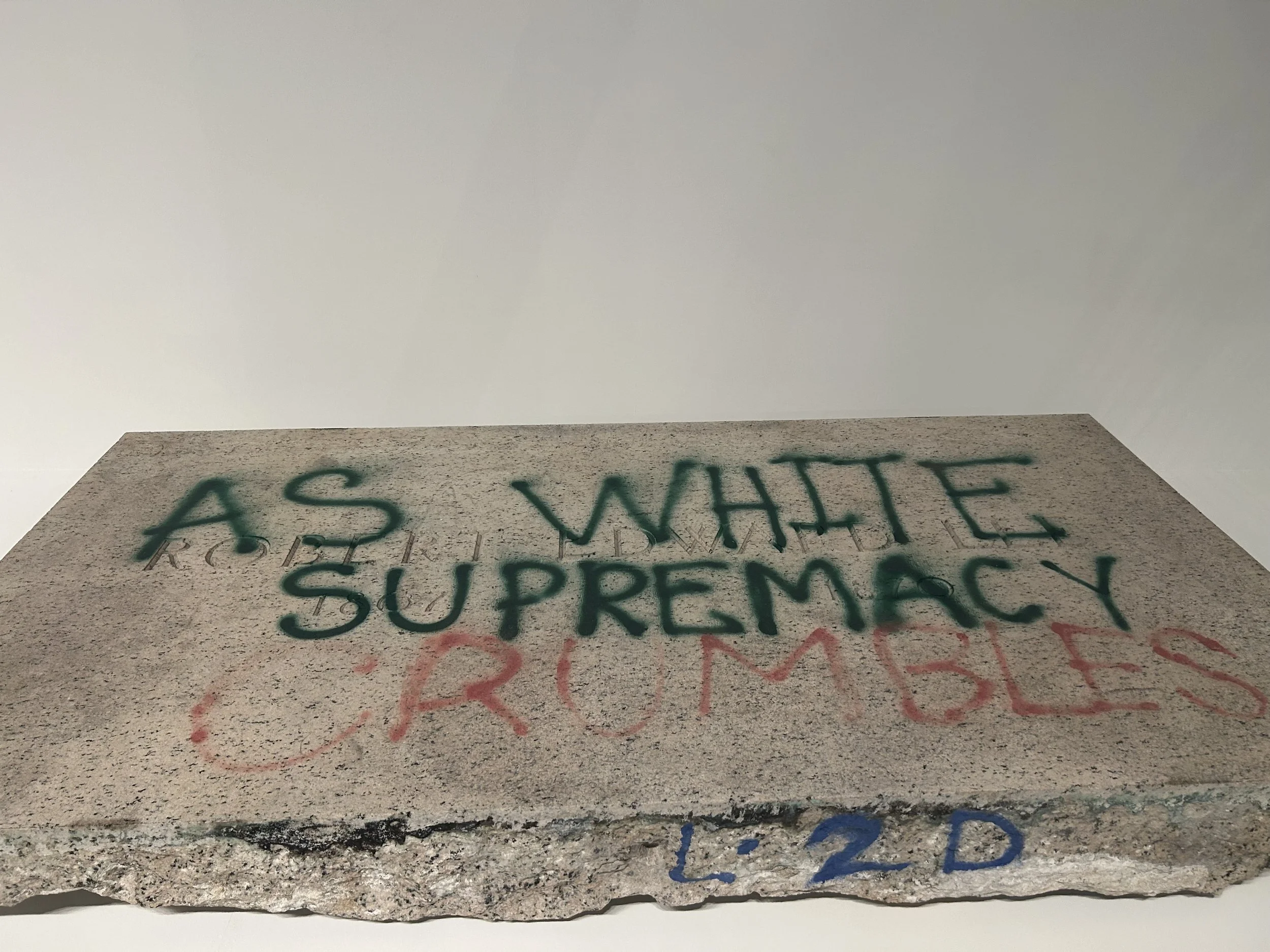

This Autumn, NOMMO attended Monuments, the Museum of Contemporary Art’s and The Bricks’ sweeping exhibition across Los Angeles, CA, that examined the Confederate mindset and its long shadow over the American imagination. Spanning the Geffen Contemporary and The Brick, the exhibition traced how the legacy of enslavement, Confederate mythology, and the “Lost Cause” narrative continue to shape the nation’s understanding of itself.

For NOMMO, Monuments was not only a study of history but a mirror for the present. The presentation revealed how symbols of the Confederacy, whether in bronze, marble, granite, cast zinc, film, or media, have long reinforced myths that normalize white supremacy under the banners of heritage and patriotism, many recently toppled by the civic protests from 2020.

At the Geffen, the scale and candor of the exhibition’s presentation were both staggering and sobering. Installations featuring retellings from D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and portraits glorifying the Ku Klux Klan forced audiences to face the violence embedded in American cultural memory. For Black viewers, the experience could be deeply triggering. Yet, within that discomfort lies power: the power to name and dismantle the myths that have defined American life for centuries.

For Black audiences, Monuments invites both pain and affirmation. It acknowledges the distortion of our histories while highlighting how Black contemporary artists, such as Karon Davis, Hank Willis Thomas, and Kara Walker, among others, reclaim public space through reinterpretation and imagination. Kara Walker’s reinterpretation of a Confederate monument in "Unmanned Drone" at The Brick effectively transforms trauma into testimony. This work asserts that America's monumental landscape has long reflected its racial hierarchies. It highlights the importance of rewriting these disrupted truths and myths in a significant way to engage in a cultural contest against the narratives rooted in apartheid.

White audiences, too, appeared visibly unsettled and intrigued by the exhibition at both locations. Many encountered, perhaps for the first time, how little the Civil War and Reconstruction are taught in American schools. Studies show that fewer than 8 percent of U.S. high school seniors identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, and fewer than half study Reconstruction at all. This educational gap sustains a selective national memory, where Confederate heroes are still honored more often than those who fought for freedom and democracy in the Union, especially the formerly enslaved Africans. Reports from 2022 to 2025 indicate that over 2,000 public symbols of the Confederacy remain standing across the U.S., including monuments, markers, schools, parks, and street names.

Exhibitions like Monuments help fill that void. They position museums as sites of civic accountability rather than aesthetic distance. The inclusion of works such as Hank Willis Thomas’s "A Suspension of Hostilities," a homage to the Duke of Hazzard’s car, which critiques pop culture’s casual embrace of Confederate symbols, underscores how these myths seep into everyday American life, specifically, America’s living rooms.

A Suspension of Hostilities, 2019 by Hank Willis Thomas

As our founder, chief curator, and historian, Tyree Boyd-Pates, reflected while viewing the exhibition, we are living through what can only be described as a cultural civil war. Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates’s We Were Eight Years in Power and The Message, Tyree noted that this cultural conflict is fought not through cannons or muskets, but through media, monuments, censored books, and the meaning itself. Each cultural battlefield, whether in galleries, classrooms, or public debates, mirrors past skirmishes and foreshadows future ones. The stakes are no longer just historical; they are existential, and that battleground is unfolding as we speak.

For NOMMO, Monuments affirms why cultural strategy matters. It demonstrates that the contest over national identity is not abstract; it is visual, emotional, and ongoing. The myths of the Confederacy have not disappeared; they have evolved into new forms. To confront them requires more than artistic interpretation. It demands collective reeducation and a willingness to build new monuments that honor truth, resilience, and the unfinished project of American freedom.

As Los Angeles continues its own reckoning with race and remembrance in preparation for the 34th anniversary of the LA Uprising in 2026, Monuments offers a blueprint for how museums and cultural institutions can become active agents in shaping public memory. It challenges us to ask three key questions: What monuments still exist within our periphery, and which deserve to be toppled or reimagined? How can we ensure that the next generation inherits symbols of liberation rather than domination?

In this moment of cultural fracture and the reinstallation of toppled Confederate monuments by our federal administration, MOCA and The Brick’s Monuments remind us that the stories we preserve determine the futures we imagine. The war for America’s memory is not behind us; it is happening right now, in the galleries, classrooms, and creative spaces where truth and myth still collide.

Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee Monument

Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee Monument